Download PDF: Richland Wilkin JPA Comments to MNDNR DSEIS

September 27, 2018

Jill Townley

EIS Project Manager

DNR Division of Ecological and Water Resources

Sent Via Email: environmentalrev.dnr@state.mn.us

Re: Fargo-Moorhead – Comments to DSEIS

Our File No. 24082-0005

Dear Ms. Townley:

I. Introduction

These comments on the DSEIS are submitted on behalf of the Joint Powers Authority for Richland and Wilkin County. The JPA represents two counties and governmental entities as well as individuals in Cass and Clay County.

There are six major issues with this project, and the DSEIS compounds and repeats those problems. In our permitting comments, we have raised a series of concerns regarding this revision to the LPP. We ask that our permitting comments be incorporated into this submission.

| • | EO 11988 Violated. The underlying flaw in this project is that it is designed to develop 40-50 square miles of currently undeveloped floodplain South and Northwest of Fargo. That generates massive volumes of extra water flow, which must either be stored in Minnesota, or stored in North Dakota, or sent downstream. The solution is to refrain from developing the floodplain, but Diversion Authority has once again submitted an alternative that continues massive unnecessary floodplain development.

As with the prior Minnesota Environmental Impact Statement, this DSEIS fails to treat EO 11988 principles with the seriousness that they deserve. In the attached Appendix, we provide a detailed exposition describing why EO 11988 must be followed to the letter by both USACE and DNR. EO 11988 is legally binding; it is an expression of sequencing principles found in MEPA as applied to flood control; and as MnDNR has repeatedly recognized, EO 11988 principles must govern environmental consideration of all flood control projects. EO 11988 principles are implemented by the executive order, but those principles are embodied in Minnesota environmental law and regulations, are integrated into numerous federal regulations, and in 2007 were incorporated into WRDA 2007. |

| • | New Proposal Project Fails the Permitability Tests found in the Commissioner’s Order. Throughout the deliberations of the Task Force, JPA repeatedly urged that any proposal considered should be measured against the criteria set in the Commissioner’s Order. Diversion Authority advocates refused to do that, and the resulting project alternative again violates those criteria.

It appears, instead, that Diversion Authority decided to design a new version of the LPP based on two core principles: (1) Diversion Authority has sought to maximize the amount of floodplain development, instead of minimizing floodplain development as the law requires (2) Diversion Authority has sought to move some of the features of the project into North Dakota in order to satisfy political statements by Governor Dayton regarding the balance of harm and benefits to the two respective states. The result is a project that design that continues the flaws contained in the LPP. Once again, MnDNR has allowed an environmental review of a project to ignore permittability, while avoiding any consideration of the fundamental principles found in the Department’s own permit decision. If DNR were to approve this project, that would be the essence of arbitrary and capricious decision making. |

| • | Improper Screening Out of the Minnesota Diversion. In the original Environmental Impact Statement, USACE concluded that the best way to divert floodwaters was to run it around Moorhead and through Minnesota. We can find no indication that MnDNR challenged the Minnesota Diversion as unpermittable at that time.

The revised permit application has failed to explain adequately why the NED – which is a billion dollars cheaper – has been rejected. At the core of this improper screening seems to be the department’s belief that it cannot screen out the applicant’s preferred project. This DSEIS illustrates the consequences: the project which USACE designated as the most cost effective and environmentally sound project does not even get reviewed, because somehow it is regarded as unpermittable, without even a citation to the statute or regulation that makes it unpermittable. Yet, in the original EIS, DNR screened in the LPP, even tough it was obviously un-permittable. |

| • | The Project is a Hydrological Monstrosity. The process established by USACE to arrive at the NED was designed to arrive at a cost-effective solution that avoids harm to the environment. By ignoring EO 11988 and its 8-step process, project proponent has created a fiscal and hydrological monstrosity. Both LPP and this variant of the LPP cost a billion dollars more. Both unleash intentional flooding across Cass and Clay County unnecessarily submerging prime farm land, homes, and cemeteries. Both surround the communities of Oxbow, Hickson, Bakke and Comstock with intentional but unnecessary flooding, requiring the construction of costly ring-dikes. Both ignore the sustainability provisions of the WRDA-2007.

This project has already purchased homes at up to double their value and even built a new private golf-clubhouse at taxpayer expense. All of this is a byproduct of abandonment of economic and environmental principles designed to incorporate sound engineering principles into water resource development projects. |

| • | Screening Out of JPA Alternatives that Preserves Floodplain. Recognizing that there was political pressure to avoid a Minnesota diversion, JPA provided alternative ideas that run the Diversion through North Dakota. (These were designated options B or C, or 30 and 31.) If a Minnesota diversion is rejected, these alternatives are workable, but they are being rationalized away, just as the one-billion-dollar cheaper alternative is being rationalized away by Minnesota. The DSEIS blows off these alternatives with erroneous assumptions resulting from inadequate investigation. Our opinion from engineer Anderson addresses these issues.

The rejection of these alternatives is symptomatic of a double standard in alternative reviews. The Department seems to feel that it must reject alternatives for any perceived flaw, no matter how small, advanced by the project proponent, but the project proponent is allowed to refine its project massively, to address any flaws using value engineering and other methods to meet objections. This double standard is illustrated by the fact that the Department adopted as disqualifying various objections by Diversion Authority’s engineers, without even attempting to contact JPA or our engineer, for a response or corrective refinement. |

| • | Failure to Engage in Consultation with Local and Regional Regulatory Authorities. The Commissioner’s order properly recognizes that Minnesota law demands that a project proponent meet all local and regional regulatory conditions. Nonetheless there has been virtually no consultation with Wilkin County or the Buffalo Red River Watershed District. All confirmed that the applicant has not engaged in the minimal due diligence required to determine what those regulatory jurisdictions would require before permitting. If DNR is genuinely committed to screening out alternatives that cannot be permitted, how then can it tolerate applicant’s failure to satisfy the permit conditions of local and regional regulators? |

II. Exclusion of the Minnesota Diversion is Contrary to Law and Policy

Despite the fact that the Minnesota Diversion was selected by USACE in the FEIS as the NED project, it was summarily excluded from consideration by both Minnesota and now the Supplemental Draft EIS. This exclusion is arbitrary and capricious, and it is not based upon law. The DEIS justifies the exclusion of the very project recommended by USACE on the following grounds [1 see footnote] :

Minnesota Permitting Feasibility. Any alternative that would not offer benefits to the state that are commensurate with the impacts to the state would be unable to be permitted in Minnesota. This is because such an alternative wouldn’t represent the least impactful solution in Minnesota (as required by Minnesota Law), and thus it would be infeasible

This interpretation of Minnesota’s “least impact” law is wrong and ill considered. Least impact is not a measure of the balance between benefits and negative impacts. Least impact applies to a project that significantly affects the quality of the environment. If it does, then least impact looks to determine whether there is a feasible alternative consistent with reasonable requirements. There is no support for the claim that those reasonable requirements bar a project because it benefits another state more than Minnesota. The issue the alternative is “a feasible and prudent alternative consistent with the reasonable requirements for environmental protection. Minnesota’s least impact requirement reads as follows:

No state action significantly affecting the quality of the environment shall be allowed, nor shall any permit for natural resources management and development be granted, where such action or permit has caused or is likely to cause pollution, impairment, or destruction of the air, water, land or other natural resources located within the state, so long as there is a feasible and prudent alternative consistent with the reasonable requirements of the public health, safety, and welfare and the state’s paramount concern for the protection of its air, water, land and other natural resources from pollution, impairment, or destruction. Economic considerations alone shall not justify such conduct.

The decision to exclude the Minnesota diversion is utterly unsupported by this language. Evidently the Department is attempting to implement an objection levelled by Governor Dayton relating to the amount of harm in the respective states. But that comment cannot displace the statute and rules. Minnesota can reduce harm to Minnesota by requiring a project that doesn’t develop floodplain.

The USACE’s environmental review found that the Minnesota Diversion was environmentally superior to the LPP, and that finding equally applies to this revised version of the LPP. In both cases, the diversion trench is shorter. In both cases, the excess water generated is less, because in both cases, floodplain storage is supplanted by floodplain development and thus the damage to the floodplain is dramatically less. The floodplain that Diversion Authority proposes to develop stores water that flows through both Minnesota and North Dakota; that floodplain is storage that benefits both states equally, and the destruction of the floodplain storage reduces the capacity of the River to carry water from both states. What is asserted by the DSEIS is equivalent to arguing that if a Minnesota factory proposes to dump chemicals into the Red River, it’s a lesser impact if it dumps the chemicals into the North Dakota side of the river or one of its North Dakota tributaries.

If MnDNR is going to take the remarkable position that the NED is not the least impact solution, it has a responsibility to identify what environmental harm is at issue. The Minnesota DSEIS nowhere identifies what the pollution, impairment caused by the Minnesota diversion. Surely it is not the project proposed for permitting in the second application is not a superior project as measured by its environmental consequences! It eliminates more floodplain. It generates more water as a result. It consumes vastly more farmland and causes vastly more flooding in the valley, and does so in both Cass and Clay Counties.

The Minnesota Diversion meets the requirement of section 116D.04 subdivision 6. As compared to Diversion Authority’s current proposal, it is:

a feasible and prudent alternative consistent with the reasonable requirements of the public health, safety, and welfare and the state’s paramount concern for the protection of its air, water, land and other natural resources from pollution, impairment, or destruction.

JPA suggests that DNR re-read this definition. There is nothing in the definition that requires the benefits of a feasible and prudent alternative to be entirely in Minnesota, or proportionately in Minnesota. There is nothing in the definition that says that one compares the environmental harm one project to another by examining only the harm caused in Minnesota. That would be absurd as applied to a river whose water flows across boundaries.

MnDNR’s attempt to justify the equivalent harm principle in the draft is nowhere supported in the record. The DSEIS seems to suggest that a cross border project that reduces all over harm to the Red River valley will be rejected, despite the fact that the overall harm is dramatically less, unless the harm is concentrated on the North Dakota side. As a constitutional consideration it is of doubtful merit, but it is nowhere supported by the statute. Pipelines go through Minnesota that primarily benefit North Dakota and states east of Minnesota. There is no permitting law, nor should there be, that asserts that needed infrastructure must be rejected because it primarily benefits citizens or residents of another state.

Minnesota law bars the LPP because it is environmentally damaging, and there are lesser impact alternatives, not because Minnesota bars construction of infrastructure that benefits other states. If a pipeline carries petroleum from North Dakota to a refinery in Ohio, it is not prohibited by Minnesota environmental law because the petroleum is North Dakota petroleum delivered ultimately to the East Coast. Minnesota law requires the pipeline to follow a route that does the least damage, one that is the most environmentally sound but it does not demand that the petroleum must be delivered to Minnesota refineries. If the Minnesota diversion is globally the safest, cheapest, least impact diversion possible, the fact that the primary benefit runs to Fargo is not grounds for denying a permit.

There may be other legitimate grounds for denying such a diversion. For example, the project’s failure to reduce impacts to Minnesota or the Red River as a whole, by failing to mitigate with distributed storage is a fair consideration. The use of a diversion to develop floodplain is a matter properly considered by Minnesota, in fact it must be. The possibility of fully protecting Fargo – as Moorhead has done – with other flood control means: these are all properly considered in the Minnesota permitting process. However, since the USACE has determined, the Minnesota Diversion is the NED project, it is arbitrary and capricious to assert that this variant of the LPP is superior to the NED. The Minnesota diversion has been improperly excluded as an alternative, both by the Federal SEIS and by the Minnesota SEIS.

The approach taken by USACE and Minnesota in this regard leads to an absurd result. A major portion of the Buffalo Red River Watershed District is to be intentionally flooded to promote the development of floodplain in North Dakota. There exist multiple alternatives that avoid this damage, and one of them was originally designated as the NED project. The record of neither Minnesota nor North Dakota proceedings offer any basis for rejecting the alternative determined to be the best, simply because there are more benefits to North Dakota.

This point is worth restating in a different way. The Minnesota Diversion was studied for several years. During that time, repeatedly the Minnesota Diversion was treated as the best option, both economically, and environmentally over and over again. It is evident that there were persons in Minnesota who opposed the project, but those comments predated the decision by the USACE that the Diversion was environmentally and economically superior. The Diversion Authority’s reimbursement on the LPP is limited to the cost of the NED—the Minnesota Diversion. That’s because the USACE has concluded that the NED is superior to the LPP, and by federal law and USACE policy, the federal government will not cost share beyond the cost of the NED project. If the NED project were not feasible, as Diversion Authority contends, neither Minnesota nor USACE would have allowed Congress and USACE to base compensation on the

NED project.

Finally, it is important to recognize that when comparing the NED to the LPP, or the second iteration of the LPP reviewed here, the ecological staff comparing these two projects are comparing a project that has experienced repeated iterations of value engineering, addition of staging and storage, installation of costly ring dikes, and alteration of the flows through town, to a project that was frozen as of the completion of the Federal FEIS. When it was revealed in September of 2010 that flood protecting 50 square miles of floodplain would increase downstream flooding, the ensuing design efforts to resolve that problem excluded the NED. Although distributed storage would reduce the downstream flow by at least 1.6 feet, no effort was introduced to improve the NED with distributed storage. It is patently obvious that DA has guided the alternatives review away from anything that doesn’t develop floodplain, and someone in Minnesota has guided the alternatives away from a Minnesota diversion. The result of this guiding effort is to give us a project alternative that is a billion dollars more expensive, which unnecessarily floods both Minnesota and North Dakota, and which is still unpermittable.

III. The New Iteration of the LPP is UnPermittable.

While the record does not support screening exclusion of the Minnesota Diversion it certainly supports exclusion of this project as unpermittable. Remarkably, throughout the task force process, and the leadership review, this project was never subjected to even

a cursory review as to whether the project meets Minnesota permitting criteria. The Commissioner’s Order should have been the baseline for any review of an alternative project but it was not. Among the key components of the Commissioner’s order are:

| • | That the project violates state and federal policy by promoting the unwise and unnecessary development of floodplain. UF-32(a). 32(b), 32(m); Comm. Order ¶ 160. This project clearly violates that requirement. |

| • | That the project is not the least impact solution as required by Minnesota Environmental Policy Act, (MEPA) section 116D.04. CL-85, UF-32l, CL-103. CL-105, CL 106, CL-109. USACE itself identified and recommended selection of a Minnesota diversion that will cost $1 billion less and avoid shifting floodwaters off of the natural floodplain and onto other communities. |

| • | That the project violates regional and local water and land use planning policy and law as required by the 1974 water law reforms passed Chapter in Laws 1974 Chapter 558 and then implemented in Minnesota Statutes Chapter 103G and its regulations. Comm Order ¶ 54-a; Comm order ¶57. See also Buffalo Red River Watershed District Docket Comments; Wilkin County Docket Comments. The Buffalo Red River Watershed District, in its comments to the permit docket once again warned that no effort has been made to initiate a dialog on regional permitting requirements. Our concerns regarding coordination efforts called for in the mediated settlement agreement have been stated previously. |

| • | That the project is overbuilt and over-engineered because it is predicated on providing 500-year protection instead of the standard 100-year protection used throughout the basin. |

The Commissioner’s order pointed out that approximately 54% of the lands removed from flooding in the project’s proposed 72,923 acre “benefited” area were “sparsely developed flood plain located outside of Fargo.” (Para 36, 154 and 196, Dam Safety and Public Waters Permit Application 2016-0386, Findings of Fact, Conclusions and Order). Throughout their justification of this massive project, both Diversion Authority and USACE wrongly describe this floodplain as “benefitted” by the project, because it would be converted from floodplain to land suitable for scattered suburban development outside the current metropolitan area. That description is misleading: under Minnesota and federal law, floodplain is not benefitted by developing it, any more than a lake would be benefitted by draining it and building a shopping center on it.

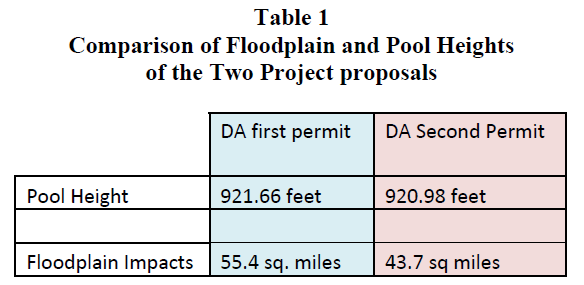

Both national and state policy call for the preservation of floodplain’s floodwater storage. Flood protecting floodplain for development impairs the natural flood handling capacity of the river basin and makes flooding worse. That, in fact, is the major problem with the expanded LPP. Once Diversion Authority decided to expand the scope of the project beyond protecting existing development and infrastructure, to floodplain development, the project no longer became permittable. This project is virtually indistinguishable from the first. Here are the floodplain impacts and pool heights compared

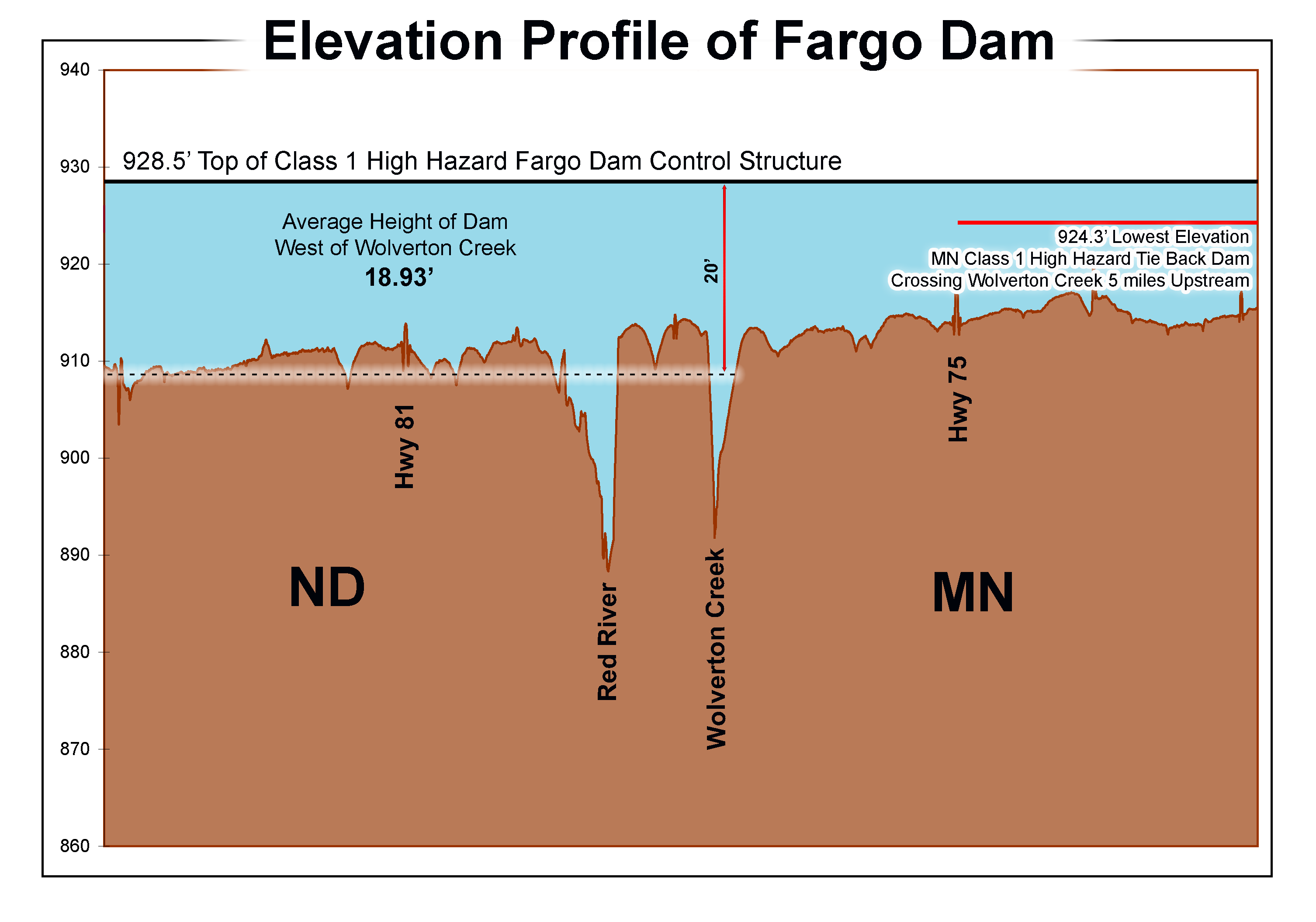

The Commissioner correctly found that the high hazard dam across the Red River and its floodplain would be built to shift the waters off of the floodplain surrounding Fargo onto other regions and communities. (Para 34, Findings and Order). The plan: “simply shifts the burden of flooding from one sparsely developed rural area to another and, to this extent, is of minimal benefit to the public welfare.” (Para 196, Findings and Order).

The Commissioner further correctly concluded that

“[t]he review of the economic analysis and flood control benefits performed for the proposed project does not establish that the quantifiable benefits support the need for the project” as required by MN statute. (Para 137, Findings and Order). “Constructing a Class I (high hazard) dam is neither reasonable nor practical in light of the incremental increase of flood protection afforded to existing development in the F-M metro area.” Id. The FM Diversion Authority failed to establish that its proposal represented the “minimal impact solution” with respect to all other reasonable alternatives as required by MN statute. (Para 85, 198, Findings and Order).

We arrive at this juncture, because the purpose of the original Diversion project was radically altered in order to promote floodplain development. The original purpose of the Fargo Moorhead flood mitigation project was crafted in conformance with federal [2 see footnote] and state sustainability policies. In conformance with these policies, the project was to be designed:

“….to reduce flood risk and flood damages in the Fargo Moorhead metropolitan area while avoiding an increase in peak Red River flood stages, either upstream or downstream and minimizing loss of floodplain in accordance with Executive Order 11988, the floodplain policy. See DNR Letter August 2010 (emphasis added).

Through a lengthy series of feasibility studies, the United States Army Corps of Engineers had developed a project design that would reduce flood risk and flood damages in the metropolitan area while avoiding an increase in peak Red River flood stages, just as the above DNR letter describes. These sustainability goals were achieved by minimizing the loss of floodplain in accordance with Executive Order 11988 and its Minnesota policy analog. Floodplain storage plays a critical role in reducing the impact of major flooding in the Red River Valley, and particularly for the Fargo Moorhead metropolitan area. The aerial photo below shows the largely undeveloped floodplain south of Fargo during the 1997 flood of record.

This floodplain to the south of Fargo and another larger floodplain to the northwest provide critical flood storage capacity during major flood events. If water must be removed from these floodplains during major floods, that makes flooding worse. Flood protecting those areas would destroy their flood storage function, and dramatically increase the flow of floodwaters downstream. That certainly is one of the reasons that the original project was designed to protect developed Fargo, but to preserve the natural flood storage functions of undeveloped floodplain south and northwest of developed Fargo.

On April 8, 2008, the USACE released a Reconnaissance Report, (Administrative Record, AR0054197) reflecting the results of years of careful study. The Report recommended preliminary project configurations with a diversion channel running east of Moorhead. This Minnesota Diversion would fully protect Fargo and Moorhead at a far lower cost than the North Dakota alternatives while maintaining the flood storage functions of the floodplains south and northwest of Fargo. In fact, the Reconnaissance Report found that only the Minnesota diversions were cost effective. North Dakota diversions were more costly and more environmentally complex, because they had to be longer and because they had to cross multiple tributaries of the Red River.

However, powerful interests on the Fargo side saw an opportunity to use federal funds to massively expand the flood control project to develop the 50 square miles of floodplain to the south and northwest of Fargo. To some extent, they used local opposition to the diversion channel as an excuse to append a floodplain development scheme to the project. Adding flood protection to the south floodplain would depart from the project constraints agreed to by interested parties but it would turn low value land into high value suburban sprawl. USACE initially ruled, correctly, that using federal funds to develop floodplain would violate the federal floodplain Executive Order, and it violates the original agreed design principles for the project.

The permit problems for this project derive directly from the Diversion Authority’s decision to violate the above described agreed sustainability principles and add massive flood plain development to the project design.

In the documents submitted with these comments, we show that Fargo simply does not need 50 square miles of expansion room. See Docket Comments of JPA, Appendix B. Fargo is already too sparsely developed. Fargo’s comprehensive plan actually calls for infill development. As Governor Burgum has stated [3 see footnote] :

Our city has an ability to grow and grow smarter than other cities by growing more densely as opposed to growing horizontally,” he told the Planning Commission. “The 52 square miles is enough to hold us for a long time.”

IV. Diversion Authority Failed to Establish Compliance with Local and Regional Ordinances.

At Finding 44 the Commissioner states that Minnesota law requires a flood control project to receive local permits and governmental approval. The Commissioner’s Order correctly finds that the Diversion Authority neither sought nor obtained those approvals. The Commissioner pointed out that the state environmental impact statement had warned

Diversion Authority that the approvals were required. That should not have been a surprise to Diversion Authority, however, because the local approvals requirement is the centerpiece of Minnesota’s water regulatory framework. The Commissioner explained:

The proposed Project would require permits and other governmental approvals, and are discussed in the State FEIS §§ 1.5 and 3.14.3. Additionally, changes to regulatory floodways, Base Flood Elevations (BFEs) or extents of Special Flood Hazard Areas (SFHAs) caused by the construction and operation of the proposed Project would require updates to the existing Flood Insurance Study Map. The NFIP participating communities with FIRMs affected by the Project would require Flood Insurance Rate Map revisions pursuant to the FEMA Letter of Map Revision (LOMR) process and in accordance with the Final FEMA/USACE Coordination Plan. State FEIS §§ 1.5 and 3.2 and App. F.

It is clear that this failure to coordinate, collaborate, and develop the project so that it meets local ordinance requirements was intentional. USACE and Diversion Authority simply applied a surface analysis and assumed, without a scintilla of legal support, that regional and local permits could not possibly be required. As the Commissioner pointed out:

In a meeting dated July 13, 2016 the DNR asked the Diversion Authority if it had applied for or intended to apply for any local government approvals. The Diversion Authority represented that it did not intend to seek approval from local governments for the proposed Project. Consistency with local government land and water plans is a required element for any Minnesota State water permit decision and is addressed in ¶¶ 161 – 197. Commissioner’s Order, Finding 53.

In prior filings with the DNR, we have pointed out that the legislative intent behind the local and regional permitting requirement was to prevent one region from diverting waters onto another region and to encourage watershed wide coordination and cooperation. Recent contacts with the major regional and local regulatory authorities confirm that Diversion Authority continues to disregard the underlying scheme of Minnesota permitting law. Their approach seems to be that since we are Fargo and have the backing of the Federal government, we can blow by regional authorities and ignore them but that is not how Minnesota permitting works.

The mediated settlement agreement was designed to create a collaborative process to allow major projects to move forward. Signatories to that agreement recognize that regions are interdependent, and that the entire Red River Valley must work together to reduce flood risk. Since Minnesota permitting law requires major projects to coordinate with upstream and downstream entities, flood control depends upon collaboration, listening and mutual concessions. To this end, virtually every watershed district in the Red River Valley has incorporated the mediated settlement process in their legally binding watershed plans. Yet, even at this late date, local regulators like Buffalo Red River Watershed District have been complaining that Diversion Authority has failed to engage in the contemplated consultative process.

The direct result of Diversion Authority’s out of hand dismissal of local and regional permits is that the project was not designed in coordination with local and regional regulators. This would be like designing a building without checking with the local building and zoning codes. Even a cursory review of the actual permitting laws and regulations should have caused Diversion Authority and USACE to recognize that the legislature intentionally barred projects benefitting one region from shifting waters onto another region, without obtaining permits from the negatively impacted region. In federal court, and in the state proceedings, Diversion Authority has repeatedly disparaged the application of local and regional ordinances to public water permitting. It argues that surely regional and local ordinances could not defeat its plan to transfer water from one portion of the state to another. How is it possible that this new version of the LPP is under review when Diversion Authority has not even conceded that the project is government by Minnesota permitting law, and when they have not yet taken the steps necessary to work with impacted regional and local authorities.

V. The DSEIS Erred in Excluding JPA Alternatives.

The record will show that Diversion Authority fought aggressively to disparage and marginalize JPA’s alternative project designs before modelling was complete. The modelling that was conducted shows that by redesigning the North Dakota diversion so that it retains the floodplain storage south and northwest of Fargo, there is massive reductions in the amount of water that needs to be stored elsewhere. At the leadership team meeting scheduled to consider these alternatives, Diversion Authority arrived with a press release announcing Diversion Authority’s unilateral selection of this alternative. Following that, Diversion Authority and their engineers have been tasked to marginalize and develop reasons why the project cannot be built without developing the floodplain.

There is a grave danger in prematurely screening out alternatives as has been done here. The primary engineering for a major project comes from the proponent. It is relatively easy for a project proponent who wants to avoid scrutiny of alternatives to raise possible difficulties or impediments to the project. All of these projects have challenges; all of them require refinement. Certainly, the LPP has been no exception. It went through years of refinement, value engineering and now this new set of refinements. The DSEIS rejects JPA alternatives projects at the screening stage, simply because Houston Moore Group has advanced an issue that needs to be resolved.

Accompanying this submission is a report by Charlie Anderson. Engineer Anderson has a stellar track record in flood engineering in the Red River Valley. His opinion derives from work on modelling and decades of experience with the Red River. The issues raised by the DSEIS have been accepted at face value without even consulting with engineer Anderson. If these concerns actually arose from a genuine desire to find the best least impact alternative, certainly the folks who raised these concerns would have made an effort to contact Mr. Anderson and discuss them. Anderson is the engineer who raised the issue with downstream impacts in 2010, when the entire engineering team at USACE and Houston/Moore neglected to find those issues. He has steadfastly offered honest opinions, and his opinions have been persistently proved accurate. It would be arbitrary and capricious to exclude the JPA propose alternatives based on the record that currently exists. These alternatives have not been fully vetted and should have been examined.

VI. The DEIS Flagrantly Errs in Counting “Structures” Impacted.

Throughout this process, Diversion Authority and their engineers have manipulated the counting of structures. JPA representatives have attempted to verify structure counts and are bewildered at the numbers advanced by the DSEIS. Structures that are already protected by existing state and federal projects appear to be recounted as needed protection. Structures that have been built in the floodplain in violation of national and local policy are treated as being at risk, even though they were intentionally constructed in the floodplain. It appears that the Diversion Authority’s structure count must also be counting structures that would be built in the future, because the structure count is otherwise inexplicable. Homes that have never been flooded appear to be treated as at risk. Areas to the Northwest of Fargo that are undeveloped are treated as having numerous structures at risk, even though they are largely undeveloped and unaffected by JPA’s proposal.

This project and its alternative version, the LPP, is designed to expand Fargo by 40 to 50 square miles. The plan is to build massively into that floodplain, so that should the levees fail to protect that newly developed area, the losses experienced by flooding will be magnified many-fold. It is absurd to suggest that this is a project that is designed to preserve protection, when in fact, it is designed to flood lands currently flood free, and build in the floodplain.

Sincerely,

/s/Gerald W. Von Korff

JVK/dvf

Enclosures:

• Materials submitted to the State of Minnesota — Executive Order 11988 argument; Fargo Comprehensive Plan; Anderson Testimony (Exhibit 1)

• Anderson Report Regarding Alternatives Review (Exhibit 2)

• Fox Submission to the DNR Leadership Team (Exhibit 3)

• Aaland Submission to the DNR Leadership Team (Exhibit 4)

[1] The FEIS also states the following: “Feasibility of Mitigating Downstream Impacts.

In Alternative 3, while the alternative meets the 100-year accreditation and would have environmental benefits over the Project, it would result in downstream impacts that would require mitigation. Given the geographic distribution of downstream impacts and the amount of water that would require storage elsewhere on the landscape, it was determined that mitigating these impacts was infeasible.” This suggestion is totally baseless. The amount of water generated by the Minnesota diversion has been shown to be dramatically less than the LPP. The suggestion that this water cannot be managed is preposterous and completely unsupported in the record with hydrological evidence.

[2] 42 USC 1962-3 states all water resources projects should reflect national priorities, encourage economic development, and protect the environment by- ( 1) seeking to maximize sustainable economic development; (2) seeking to avoid the unwise use of floodplains and flood-prone areas and minimizing adverse impacts and vulnerabilities in any case in which a floodplain or flood-prone area must be used; and (3) protecting and restoring the functions of natural systems and mitigating any unavoidable damage to natural systems.

[3] He continued: The city has 3.7 residents per acre, a far cry from the 10.7 in 1950 when it followed a traditional growth pattern that preceded suburbanization. The kind of suburban development where people need to drive everywhere is becoming less popular nationally, Burgum said. A 2013 survey by Realtors found that 55 percent of American adults would prefer a house within walking distance of stores, restaurants and schools to a house with a big yard, he said.

Views: 717