The FMDam.org family is still growing with membership nationwide.

We encourage comments to the issues presented.

Of special interest is the recent concern expressed that “differences in opinion appear to be based on a different set of beliefs on what the facts are.”

I will not quibble with the opinion of the subscriber.

Dealing with facts, trying to keep a distinction between the “facts are facts” and the “beliefs of what the facts are” is a constant struggle.

For a look at the facts and opinion of the history of development on the flood plain of the prehistoric Lake Agassiz lake bed, see:

Article: Red River on the Rampage

|

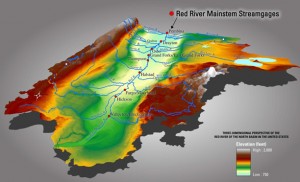

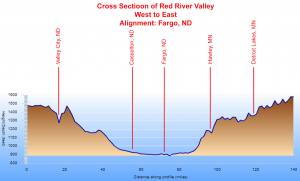

Reprinted with permission: Ross Collins, Ph.D. (University of Cambridge, 1992) Professor of Communication – NDSU Red River on the Rampage By Ross F. Collins The first well-documented attack was launched in April 1798. The victim was Charles Jean Baptiste Chabouillez, a fur trader. From his home in Quebec, Chaboillez had pierced more than 1,000 miles into ragged wilderness in search of valuable pelts for the North West Company. Finally he set up a post on a dirty, sleepy, docile stream surrounded by a tabletop of flat prairie. And there he wrote a daily journal. It became the beginning of recorded history for Pembina, North Dakota, the first settlement on the Red River of the North. In daring to invade the vast flood plain belonging to the Red, Chaboillez became one of the Valley’s first recorded flood refugees. “The water very high and still rises,” he wrote in his journal April 8, 1798. April 12: “The water rose very high in the night. We were obliged to carry out all the goods, etc. out of the fort. Lost a keg of high wine in the cellar. The water came up to the floor in the night.” April 17: “The water rose a great deal since two days, over the square of the house (stockade). We are very short of provisions.” Chaboillez was forced into a canoe, the only practical transportation, and presumably moved his property to higher ground. Finally, the water ebbed back and left him in his sodden post. The geological history of the Red River Valley is like the Biblical story: It began with a great flood. The flood swelled to a great inland see of freshwater 12,000 years ago, a see fed by the gush of icewater form the melt of the last glacier. The weight of the retreating glacier tipped the land toward the north, so as it melted, the runoff would not drain away toward the Gulf of Mexico. Instead it pressed back toward the glacier, but the ice blocked the flow. Water could go nowhere but back onto the land, to form vast glacial Lake Agassiz. The lake–really a natural reservoir formed by the dam of glacial ice–reached out 50 miles wide in the upper valley around Fargo, the largest freshwater lake on the North American continent. From that glacial lake, which finally drained north as the ice retreated, came the flat basin of the Red River Valley. All that remains is the poky Red River and its tributaries. But when the Red Floods, it keeps the spirit and tradition of its ancient predecessor, for valley inundations can be blamed in part to the same block that build Lake Agassiz–ice. Because the river flows north, climate is it springtime adversary. Ice and snow melt first on the southern reaches of the river. The bulge of runoff pushes toward Canada, but up north the Red is not yet ready for a springtime thaw. Down river is still a block of ice, and like the glacier, it dams the runoff from the south. The Red is forced into temporary retreat, across the bottom of old Lake Agassiz. Unfortunately, we’re living on the lake bottom. The bottom is flat as a floor, so the water oozes into nearly everywhere. No flash floods on the red–it’s “one of the few rivers in the world that can run amok while practically standing still,” observed Vera Kelsey in her 1951 Book, Red River Runs North! Valley flooding is aggravated by the land’s clay floor only a few inches under its rich topsoil. The clay is as impervious to water as greasy grit, and it encourages floods to loll atop the land where it gets into trouble. Floods have defined the valley, not only in its geology, but in its history. Early settlers were slow to build in the area for fear of floods, especially in spots like the site of Fargo “Because of the floods and quagmires,” wrote the late journalist and historian Roy P. Johnson. (It took many loads of fill to dry up downtown.) Early settlers of the Selkirk settlement, now Winnipeg, were driven away by flood, and their flight from the Red at its destructive worst helped found a new city, one which in its later years has become more well known–St. Paul, Minnesota. Chaboillez’s writing was one of the earliest flood accounts, although other explorers talked of major floods in 1776 and 1790. But the first flood that really caused trouble was May 2 to June 15, 1826, the “Great Red River Valley Flood” (not the last flood to be awarded the title). It hit the Selkirk settlement. Lord Selkirk of Britain had believed early I the last century that land around the valley would support a settlement of pioneers. Accordingly, he obtained a grant of Red River land from Hudson’s Bay Co. and, after paying off Indian claims with tobacco in 1817, he persuaded a coterie of immigrants from several European nations to settle at the confluence of the Red and Assiniboine rivers. Lord Selkirk named the new settlement–which went through several names changes before agreeing, in 1873, on Winnipeg–Kildonian. But he died in 1820, and was therefore lucky enough to miss word of the flood that nearly wiped out the settlement six years later. The flood of May 1826 drove the townspeople to a wooded ridge east of the village, where they shuddered in the cold spring wind and watched the miserable waves and ice floes tear through every bridge, every building in Kildonian. They could not return to the remnants of Kildonian until mid-June. About 450 of the settlers decided then they’d had enough of the Red River, and on June 24 these pioneers left for points south, toward Fort Snelling. There they became part of a new city, St. Paul, Meanwhile the settlers more patient with the fits of the river rebuilt new settlements two miles north. Capt. Samuel Woods, in command of the Pope-Woods military expedition to the Valley in 1849, wrote of settlers who told him that during the 1826 flood “there was not a single point not covered with water.” Woods concurred, noting, “I saw evidence of the overflows in driftwood out on the prairies.” By 1861 the upper valley was at the dawn of a settlement boom. Trails of big-wheeled Red River Carts creaking from Fort Snelling to Fort Garry were well-rutted, and a few settlers–like Charles Slayton’s group near the sit of Moorhead, Minnesota–had set up cabins years before. These new opportunity seekers gave the flooding Red a chance to do more damage. On June 13, 1861, George W. Northrup, a scout employed by a steamboat line, wrote to the St. Cloud, Minnesota, Democrat, a dispatch under the dateline “Georgetown, Minn.” It read: “It is remarkable that, visited as we have been with one of the most destructive floods that has occurred in the valley for years, that the fact should not have been chronicled in the newspapers long ere this!… From the mouth of the Sheyenne to Lake Winnipeg…the valley at one time resembled an immense sea, to which, looking from any point on the Red River, no boundary could be defined, except perhaps to the eastward, in which direction the heights of the Mississippi could be faintly discerned. The long black lines of timber, marking the course of the river, and its tributaries, stretching out into the plains, were the only landmarks.” The “immense sea” stayed two weeks, but at Georgetown, then set to the north of the present city, the Hudson’s bay Co. post itself escaped the water. It was built on a knoll. Other early settlers treated the danger of inundation the same as Hudson’s Bay did–they built around it. R.M. Probstfield, who selected his farm site in 1859, found high land in Oakport township, and was never flooded away from it. He did not, in an 1876 journal entry, however, that most of the land around him was under water, and he was forced to make a roost for his hens and roosters in a shanty attached to the house, because it was “the only dry place I could find.” Of the settlers who had not quite as much foresight, their plight was predictable: the Daniel S. Johnstone expedition to Breckenridge, Minnesota, reported that between March 15 and April 12, 1857, they slogged through rising floodwater to hastily dismantle their cabin so they could rebuild on higher ground. But the damage had hardly begun. After the U.S. Civil War, with the passage of the Homestead Act, the branching out of railroads, and the prospect of riches around the fertile “Nile of the North,” settlers poured into the valley. So did floods, periodically. In an 1877 flood, settlers had to tie down small buildings to keep them from floating away. And by 1882, the North Dakota-Minnesota border twins of Wahpeton and Breckenridge, Fargo and Moorhead, Grand Forks and East Grand Forks had become well-established prairie communities. Buildings hugged the river bank, and land speculators looked to buy more property. But the Red was to put a temporary damper on land speculation the spring of that year. About the middle of March, “four feet of snow fell in a continuous storm,” wrote Johnson, quoting Caledonia, North Dakota, residents. “Warm weather followed, the sun melting the entire fall in little more than a day.” Valley people braced for what was certain to follow. On April 11, the headline of Fargo’s daily newspaper, the Argus, boasted, “The noble Red on a grand rampage and showing itself as big as the Mississippi or any other river.” The accompanying report noted that not only were “some Island Park residences in bad shape,” but in Moorhead, “the houses drowned out are too numerous to mention.” News columns also admitted, “There is considerable surplus moisture in the basement of the Argus office….” Many area structures that year were entirely engulfed. The Argus reported that on one house, “only the ridge board of the roof remained out of water, and upon this were packed about a dozen hens, patiently waiting for their webbed feet to grow that they might swim off.” This kind of humor by the 1880s was well-established among the valley’s flood-weary residents. The Argus reported that the office of the Fargo Insurance Co. was “navigable,” and “over the entrance hangs a placard with the inscription: ‘Free bath houses. Collectors can walk right into the office with their bills.'” The paper later reported that in Grand Forks a pontoon bridge was swept away, and 500 families were driven from their homes. To that, there were a few more jokes:

Nearly 100 years later, during the flood of 1969, some of that same spirit resurfaced, even if the jokes were updated. For instance, quoted the Fargo-Moorhead Forum in an April flood story: Red Cross comes to help man flooded out in south Fargo. He says, “We gave at the office.” Norwegian sits on dike with toothbrush. What for? Waiting for the crest, you know. Enderlin, North Dakota, man yells to wife, “You know that picture of your mother? Well, I put it down in the basement before it flooded!” Clearly the jokes, like the floods, had gotten no better in a century. During the last few years it seems the reaction of other cities to the valley’s flood misfortunes has been seriously sympathetic. Not necessary so century ago, however. the Argus reprinted a dispatch from the Bismarck, North Dakota, Tribune about the 1882 flood, which read, “Upon reaching Fargo, the flood [sic] put out the fires in the locomotive. The country between Casselton and Wheatland is a lake. The Grandin grain elevator, located on the river bottom, was almost out of sight Monday morning (April 10)…. We wonder if the citizens of that frog pond will continue to tell the immigrants that Bismarck is so dry that nothing can grow there.” And the Brainerd, Minnesota, Tribune noted, “No, dear Fargo, our warehouses and dwelling places are not swimming over the prairie, and we do not have to wear rubber boots from March to May.” In response, the Argus commented, “There is nothing more soothing, and drying than the tender expressions of sympathy and regret that are pouring in from every side….” The valley dried out from that inundation, but the promise of another, perhaps greater, flood menaced settlers. The Argus called the flood-prone valley “Venice of North Dakota.” Maybe that was a bit of an exaggeration, but more appropriately, settlers could have called their home “Netherlands of North Dakota.” Like the low-lying Dutch farmland, and the farmers’ fight against water, early valley farmers faced summers of recurring mud and swamp on what they called “the flats,” that is, the bottom of the former lake. Nearly two-thirds of valley land was subject to periodic flooding, noted Hiram Drache in his book, Challenge of the Prairie, and the poor drainage made the potentially rich soil useless to agriculture. First settlers, like Probstsfield, simply avoided the low spots, but later settlers knew a better answer had to be found. The answer was drainage. The valley’s railroad builder, James J. Hill, was one of the first to appropriate money for a system of ditches, and by 1908 the Minnesota legislature followed. To the north, where the problem was even more severe, Manitoba government appropriations led to a system of 1,342 ditches by 1920, Drache reported, drying 350,000 acres of farmland. On the U.S. side, an extensive drainage system controlled by county drain boards reclaimed wetland for farmland, as Holland’s system of dikes and pumps reclaimed land from the sea. Not that some of the drainage wasn’t criticized; detractors say the ditches hurt wild rice crops and natural wildlife habitats. But ditches do little to stop floods. In fact, some critics say they’ve made the Red more flood-prone, although the chronicle of devastating floods in early valley history seems to indicate that civilization has not aggravated the natural inclination of the river. The greatest flood of the 19th century–and perhaps the greatest of modern times in the valley–poured in during the spring of 1897. The water was so high that tributaries and the Red merged into one vast lake. “From the cupola in the courthouse in Breckenridge, one saw only water and a few knolls in every direction,” wrote Drache. The steamboat J.L. Grandin, last memory of the age of steam on the Red, broke loose form its mooring, floated downstream to inundated land near Halstad, Minnesota, and rested farm from the riverbank when the water receded. Its timbers rotted there for years as a last reminder of riverboat days. Major floods drenched the valley periodically in the first half of this century, including 1907, 1916, 1943, 1947, 1948, 1950 and 1952. That last flood left St. John’s Hospital in Fargo with $220,000 damage. the 1948 flood cost Grand Forks and points north residents $10 million. The 1950 flood drove 100,000 people form their homes in Winnipeg, and left $17 million in damage. In all, flood damage caused by the Red in Minnesota alone between 1945 and 1955 was estimated at $25 million, according to a 1959 League of Women Voters study. Upper valley residents decided something had to be done. They petitioned the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which offered a program of flood control to cost more than $11.5 million. The federal government promised to pay more than $9 million of that. By 1959 the corps had built flood control dams on the Ottertail River, the Sheyenne River, the Park River, the Red Lake River, and Lake Traverse, plus several levees. The corps also constructed levees at Fargo and Grand Forks. All of that was a comfort to residents–until 1969. In January of that year meteorologists were already giving warnings that snow cover was dressing up the Red for another rampage. By April communities along the river had already stockpiled sandbags. Unfortunately, two days of rain April 7-8 set the stage for a flood rivaled only by the great flood of 1897. The army corps moved in to push together 80 miles of emergency levees, and these dikes plus sandbags–five million were used in Fargo alone–saved hundreds of structures. An emergency dike even saved Fargo City Hall from inundation. The city of Kragnes, Minnesota, was an island, and the entire city of Perley, Minnesota, was under water. A Fargo-Moorhead Forum reporter wrote of a boat ride through Perley: “The outboard motor struck bottom only at a few high points as the boat cruised up and down streets.” The flood covered 90 percent of the valley. Along with some grim jokes about “waiting for the crest,” some angry residents tried to pin the blame. In Grand Forks, homeowners blamed the city for refusing to protect them. But finding scapegoats for floods is nothing new: during the 1882 flood, some residents blamed Northern Pacific Railroad for driving bridge pilings into the river, which supposedly blocked the free flow of ice and water. The valley was not to escape several floods in the last decade, either, including one in 1975 unrelated to ice dams, when a torrent of rain in mid-summer puffed the Red into a lake again. And yet, most of the year, the Red is sluggish, muddy, mild-mannered. In fact, in 1932 and 1936, it dried up completely in spots. But that is deceptive, as author Kelsey reported in an anecdote to introduce her history of the valley. Working as a guide to a visiting U.S. dignitary in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, Kelsey told the man she was from Grand Forks. “And how’s the raging Red?” he asked her. “Oh, he’s the same quite, wriggling stream he always was.” ” Quiet, nothing!” the man retorted. “In flood, he’s one of the most dangerous and destructive rivers in North America.” The man had lived in pre-1900 East Grand Forks. (This article originally appeared in the Red River Heritage Press, 1984.) Copyright 2004 by Ross F. Collins |

Views: 4543

This article paints a pretty clear picture that keeping the water out of the valley while the water thats there drains is the best bet.

Building a dam in the middle of the lake surely doesnt protect the valley and seems foolish and selfish of the diversion authority.

The billions they want to invest would be more just if it protected more of the valley.

An interesting and insightful review of the

Red River settlers